I wanted to write a post to mark the Academic Writing Month of November (yes, it is a thing). I don’t know who decided this was a good month for writing. November is not a particularly auspicious month in the academic calendar. Perhaps it comes at a time where that first sting of term has (supposedly) died down, and we might turn our attention to all the writing projects we have been neglecting.

In any case, it is now that #Acwri comes alive, and things like NaNoWriMo (for novelists, but academics can use it too) get underway.

It is a good excuse for me to talk about my favourite writing subject - social writing - and give a shout out to my writing buddies (hello to Susannah and Marieke) without whom I am certain much less writing would have taken place in the last couple of years.

Why do people fear social writing?

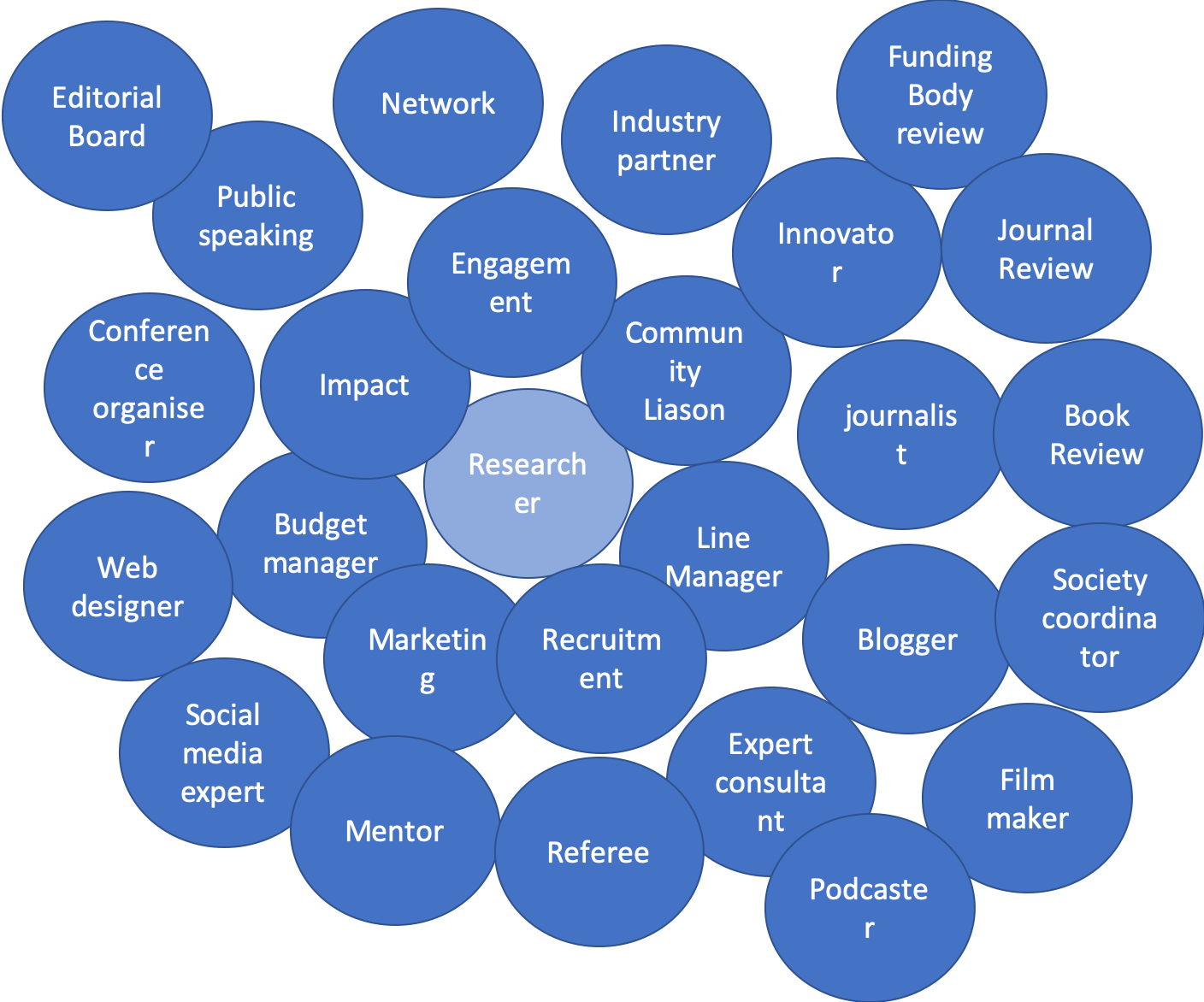

First though, I must convince you on the efficacy of social writing. Alot of people work in (largely) sole author disciplines so by and large do not write with other people. Writing has been formulated as a solitary and private space where the small sparks of joy are enjoyed and the deluge of fear, doubt, shame, avoidance and procrastination are endured. Many academics (of a certain age) dismiss the possible benefits of social writing out of hand - they never learned to do it as a PhD, therefore, it can’t be real.

I know that doesn’t sound very much like a scholarly or evidenced based reaction. Nonetheless, I do encounter this kind of reaction in response to my coaching suggestion that social writing might just be the key to getting unstuck. It might be the first step in medicating the malady that ails them.

The reason for this out-of-hand rejection is simple; people want to keep their fear, shame and procrastinating habits private, because the overwhelming feeling they have in relation to writing is shame. I get it, I really do. But the only way out the other side is through. What you are doing isn’t working, so why not try something new.

Research shows it works

Regardless of scholarly discipline (science to humanities), research shows that academic productivity increases as a result of social writing. Social writing can be enacted in person (difficult now of course) and on-line. It can be done in physical or on-line writing retreats, writing workshops or informal (or formal) writing groups set up within departments, amongst colleagues, or can transcend departments, Universities and disciplines. My own social writing groups are across different countries, Universities and disciplines. The key is to try lots of different methods until you find the mix that works for you. I had a few brushes with social writing that really didn’t work for me but eventually I got there.

Why does it work

Social writing enables accountability, visibility and shared learning. It enables solidarity in the same struggle which no-one except another academic can really empathise with. It centres your writing in your academic life, and gives you the opportunity to talk about your on-going projects in a pragmatic fashion (today I am doing X to move my article forward). It provides an opportunity to make an appointment with your writing that involves other people: this means that you will show up. The shame of being a flake is weightier than the shame of not writing.

The key to all this is to find writing buddies that WILL show up and who, like you, prioritise their writing. These might not be your closest friends and allies, and in some ways, it is better if they are from outside your department because you will not be tempted to rant about the latest office debacle in a precious writing slot.

So, if you have never tried social writing before, do give it a whirl. It is the gift that keeps on giving.