This is the third in a series of blog about academic writing in the time of Covid 19. Whilst much traditional writing advice is still absolutely valid, it needs to be placed in an entirely new context that raises particular challenges. The tenth blog will transition from Covid to deal with academic life beyond Covid and how this time is likely to accelerate changes we have already seen in the last few years.

First steps: Your new reality

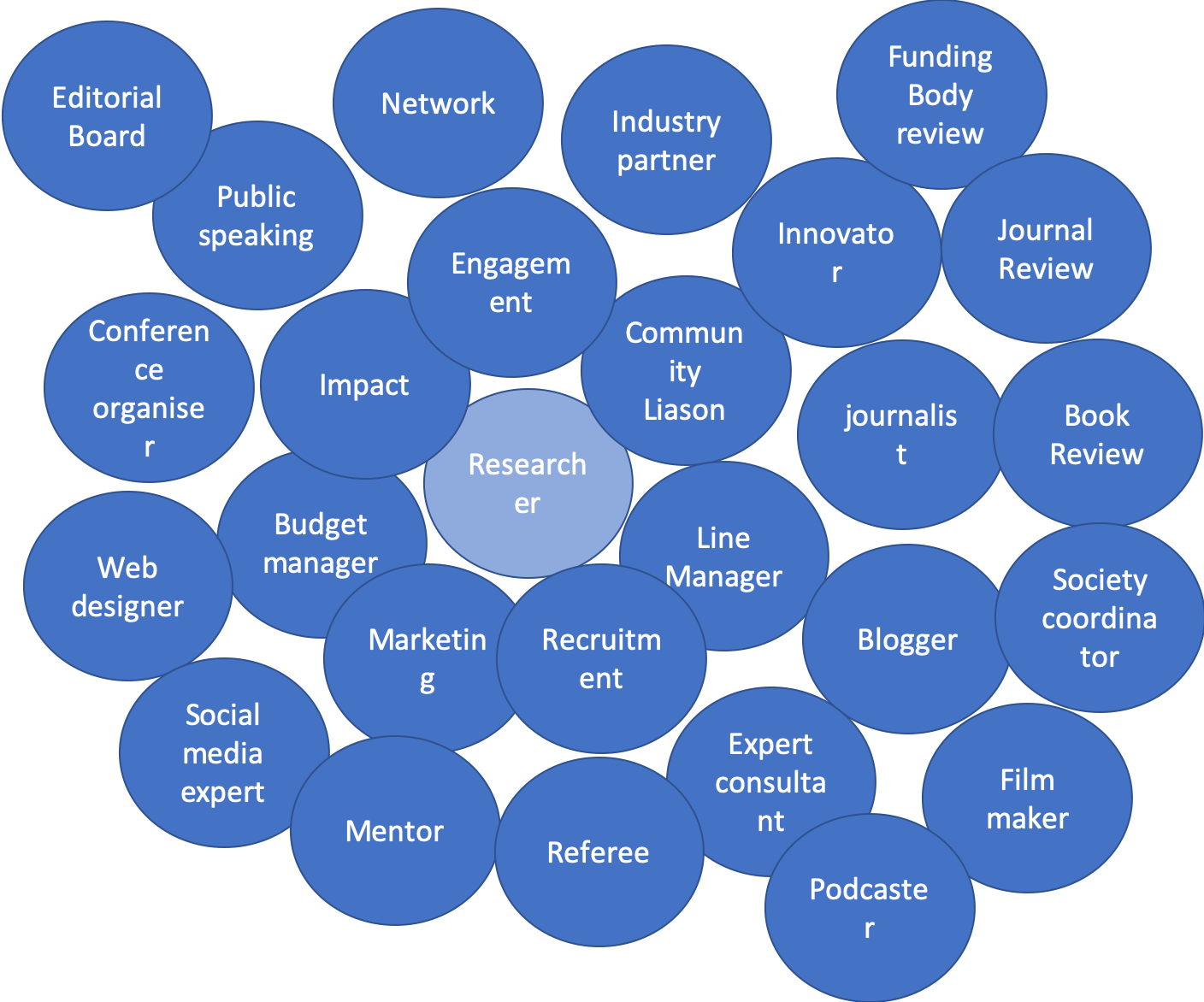

The mission of the Academic Coach is to create happier writers. The emphasis is on the happier. For some, this means more productivity, more efficiency or more elegant prose, but for others it is about having a more balanced relationship with the research /writing aspect of your career. Having time to write that is not late at night, at weekends, and in place of holidays. Whatever happy means for you, there is no doubt that your ability to do research in 2019/2020, and 2020/21 will have been (and will continue to be) severely compromised for a variety of reasons. A global pandemic and its associated trauma, including but not limited to sickness of you or your loved ones, home-schooling, lack of childcare, a complete shutdown of your research lab and/or research methodology are just some of the reasons that writing and research might grind to halt. Besides the fact that the world as we know it has completely changed, and a toothache can become a significant life altering event.

Even if you were a super productive, happy writer in 2018, things might have drastically changed.

Your new reality is something you need to face head on. I know it is tempting to sit and scream that it is all just so unfair. I feel this deeply. But, alas, reality is still there at the end of the tantrum. Facing this reality is the key first step to moving forward.

Your truth matters

One of the key components of the regular Academic Coach writing course is facing the truth about you, your life, and your writing (or procrastinating) habits. Facing this truth has never been easy, and when colleagues come to the part of the course which challenges them to record what they do all day, and record how long each aspect of writing and researching takes, they tend to shy away. Why? Because it is hard to face up to your perceived failings, and hard to look the cold hard facts in the face. Conversely, it is sometimes dispiriting to find out that the component parts of creating a finished piece of writing actually just take a really long time. In fact you are not lazy or procrastinating, it just takes ages.

Because knowing is hard. Denial is easy.

That denial underpins many bad writing habits that we too easily ascribe to our ‘unique’ style of working (I can only write when…….). We spend a lot of time debunking this nonsense on the course, either practically or psychologically, in order to move into a space where we can accept our particular reality, and create writing routines that fit into that reality as opposed to actively work against it.

Everyone’s reality is different, yet we are all measured professionally by indicators that were designed for and therefore favour the old school norm of the single white male scholar – or the married with a stay at home wife scholar – both of whom are utterly devoted to the singular pursuit of publishing. This is exceptionally tough on those who are not in either of these categories. The pandemic has only underlined this situation with research demonstrating male authors increased submission of articles and female author submissions dropped off a cliff . This isn’t news. Yet…yet…somehow we fail to accept this single truth of academia and continue to hold ourselves to standards that have no relation to our own lived realities.

This is the shaky foundation of the unhappy writer.

Face facts

So, the first critical task in order to get back to your writing and research is to face your new reality. This reality might mean children at home all the damn time. Even if we are now technically in the summer holidays (in some places), your usual summer childcare arrangements will most likely be null and void. Granny is off-limits and so on. Even without children in the house, we face separation from family and friends and leisure, and perhaps we have another body permanently in our workspace (flat mates, partners) who would normally be at work. Our partner (or us) might be a key worker. We might not have a proper workspace at all – a rickety chair, a bad back and a kitchen table.

This might go on for many, many more months. All our coping habits have been removed.

These things pose significant challenges to writing. If you normally go to a lab and now you can’t, all your research might be compromised. Endless zoom meetings about absolute nonsense will fill your calendar. No doubt, you are being subject to the ‘will we, won’t we’ two-step of on-line or face to face teaching come September, and the associated disruption that brings. You are probably preparing on-line and in person teaching simultaneously while jumping through endless administrative hoops that try to run you over like a big giant evil trucker every single day. This may well go on and on until September, when student fees have been collected for tuition and accommodation, and the cold hard reality of crumbling, crusty buildings that allow zero social distancing will intervene and settle things. For a while at least.

This stuff is stressful. I mean really, mind-bendingly stressful. Preparing courses takes time and energy, and you are not being given any time and you are all out of energy. Writing everything from scratch for September in a vastly different format: nightmare. You are probably being told there will be job losses, pay cuts, more teaching, less (if any) research time. You are probably still working out how to say no to online meetings, or whether its impolite to have the camera off (I marvel at people who care about this: they are clearly nicer than me). If, on top of this Armageddon, you or your dependents have particular health, caring or disability needs, these are surely not being met either by the health and social care service, or your institution. Stressful doesn’t really cover it.

All of this is an awful, incomprehensible nightmare. But once you have faced your new reality, instead of trying to operate as if nothing had changed, as if its ‘business as usual’, you will (after the shock) feel calmer in knowing that certain compromises will have to be made and some uncomfortable choices that perhaps fracture our ideals of what it is to be an academic will need to be accepted. This is part and parcel of the Academic Coach writing course in normal times because sometimes the things that hold us back the most are based on an internal narrative about how things ought to be, rather than how they really are.

Here there be dragons

We are now in a place of uncomfortable ‘not knowing’. We are at that point on ye olde world maps that proclaims ‘here there be dragons’. And for good reason. You don’t exactly know how things are going to pan out. Worse still, you know it’s likely going to be unpleasant and chock full of unrealistic expectations (from you, and your employer). This is taking up brain space. The worst part is you will have to be your own advocate, mentor, and champion. What I have learned from running Academic Coach is that most academics absolutely suck at being their own advocate, mentor, and champion. But you will have to. We are all drowning, not waving, and you will be fortunate indeed if your usual support groups have the ability to reach out and support you. No-one is on the life raft.

Nothing short of your physical and mental well-being is at stake here, and rest assured, your institution does not care one jot for either.

This I know is all a bit depressing.

Over the next few weeks Academic Coach will provide a series of blogs and vlogs to help you navigate this new reality. There will be some hard talk about Universities in the time of Covid, and some strategies offered for caring for yourself and your writing practice in the midst of this new environment.We will cover topics ranging from rescuing stalled research to planning in the midst of the unknown. I hope you will find these useful scaffolds for building a happier writing practice.